Passengers stories

by their descendants.

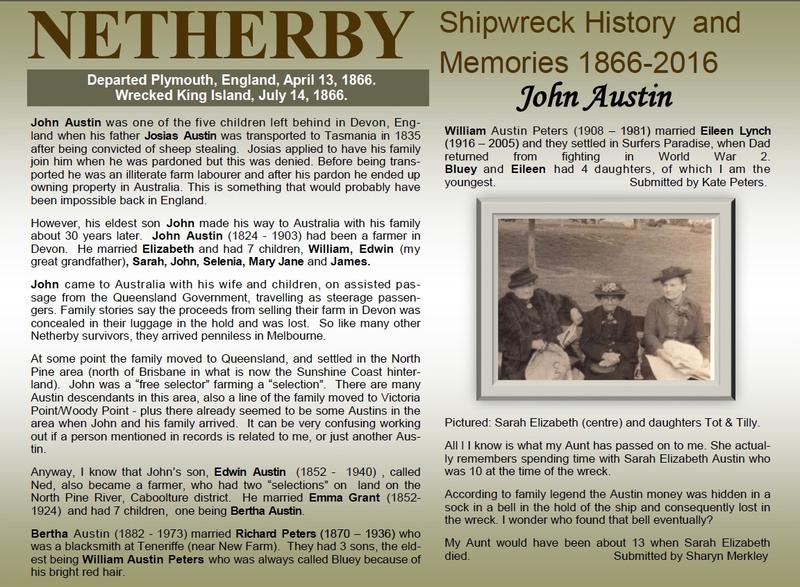

John & Elizabeth Austin & family

The story of: John and Elizabeth Austin (nee Heard), and childfren: William 16 years, Edwin John 15 years, Sarah Elizabeth 10 years, John Henry 8 years, Selena 6 years, James 5 years and Mary Jane 4 years.

John Austin 38 years, his wife Elizabeth (nee Heard) 40 years, and their seven children William 16 years, Edwin John 15 years, Sarah Elizabeth 10 years, John Henry 8 years, Selena 6 years, James 5 years and Mary Jane 4 years embarked on the Netherby as steerage passengers under Queensland’s assisted immigrants scheme to settle and take up land in Queensland. However, the passenger records show incorrect ages for the parents and the eldest two boys, allowing William and Edwin (born 1850 and 1852) to pose as adults of 24 and 21 respectively, and thus able to claim selections of land. The parents’ were both adjusted upwards to 45 years to allow for adult children. This advantaged the family while complying with the age requirements of the assisted imitation scheme.

John Austin was one of five children left behind in Devon with their mother Catherine, when John’s father Josias Austin was found guilty of stealing sheep in 1835 and transported to Tasmania as a convict. Josias was an illiterate farm labourer, who lived in and near the small village of Sampford Courtenay, Devon all his life, as had several generations before him. He had married Catherine Harvey, another illiterate farm worker, in March 1820. Josias and two friends had stolen, butchered and hidden the meat from 2 sheep looking to feed their families. They were all sentenced to transportation for life on 17 March 1835. Josias arrived in Hobart, Tasmania in December 1835 and was assigned to work on Woolmer’s Estate, a handsome sheep property. Josias was later pardoned and applied to bring his family to Australia. When this failed, he moved on and married two ex-convicts in succession, becoming a significant landowner in Invermay (now a suburb of Launceston) dying in 1883. This rise from illiterate farm labourer to land owner would have been highly unlikely in England.

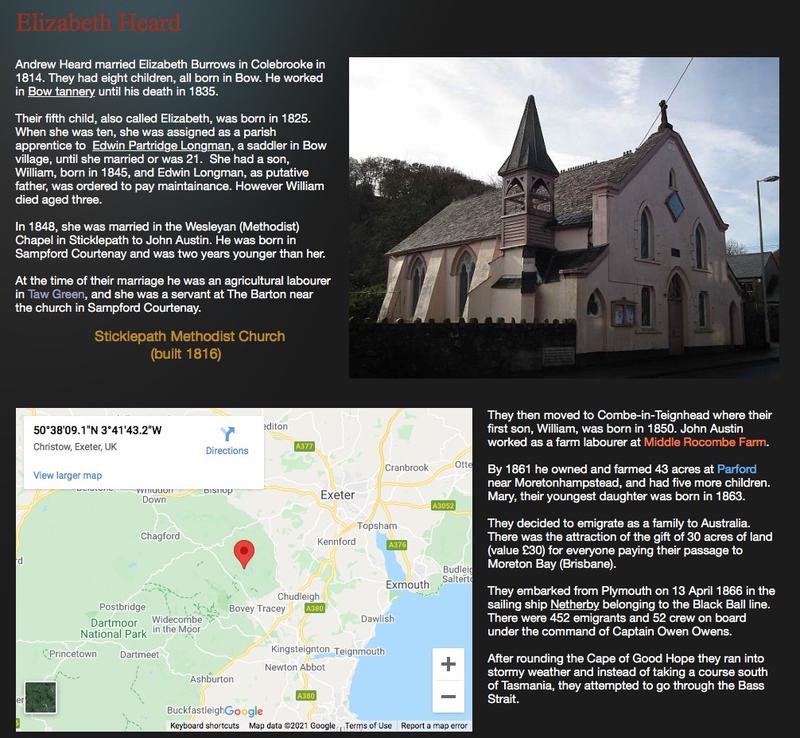

In England, his son John Austin was clearly driven to better himself and his family. He had seen his father arrested and Josias’s transportation left his family destitute. Catherine had five children - Mary Anne 14, John 7, Sarah 5, James 3 and William 1 and relied on family and friends in the tiny village of Sampford Courtenay for charity. In 1841, Catherine and the two youngest boys, James and William were living in housing for the poor in Sampford Courtenay. Sarah was with relatives in nearby Sticklepath. Mary was working at Brook Farm in Sampford Courtenay. John, aged 13, was a farm labourer, living in Sampford Courtenay with other labourers and James and Sarah Harvey at Harvey’s cottage (still known by that name), possibly Catherine’s relatives. By 1851 Catherine had found work in nearby South Tawton.

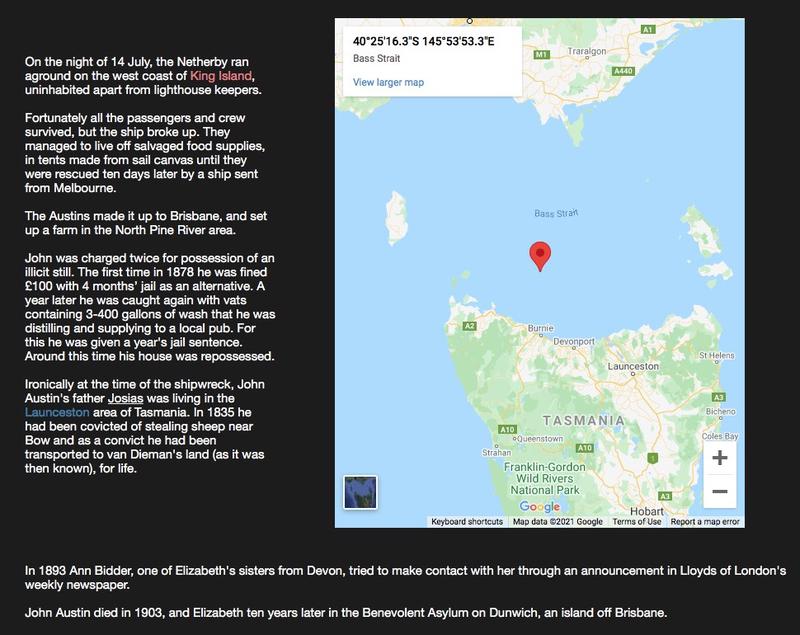

John made his way from labourer in his home village, to working on farms in two other Devon villages. He helped his siblings to support his mother. By 1861, he was a tenant of a small farm of 43 acres in Moretonhamstead, Devon. However the landlord offered the property for sale. In 1866, he disposed of his interest in the farm, and left for Queensland with his wife and children with the lure of 30 acres of land per adult (male) passage. They left on the Netherby from Plymouth on 13 April 1866.

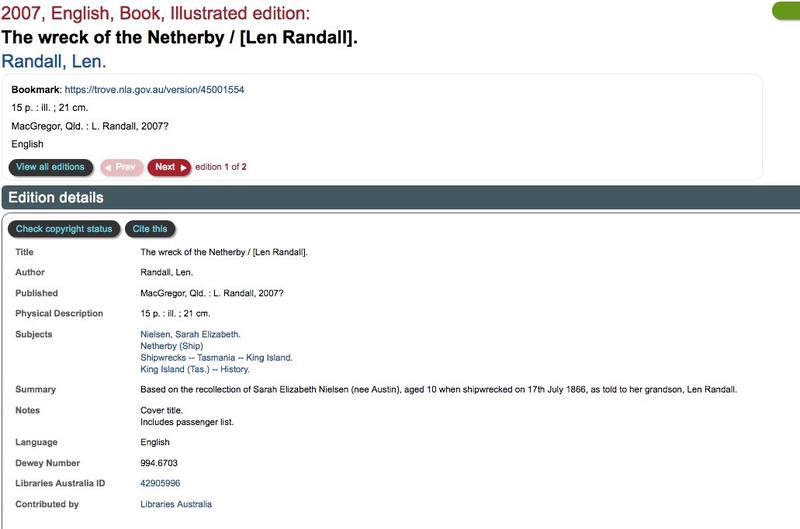

His daughter Sarah Elizabeth (10 years old on the Netherby) described these events to her grandson Len Randall, who wrote a book based on her recollections.

“Father had heard of all the marvelous land grants that were being offered to those who had the courage to help pioneer the new land, Australia. He said he couldn’t see much future for us if we stayed where we were. I kicked up a bit of a stink. I didn’t want to go … but it didn't do much good.”

They took their dray and harness and furniture, and concealed the 300 gold sovereigns from the sale of their property in a sock, in a shoe, in a bell, hidden within the luggage. After the wreck John Austin tried to retrieve this from the hold but was prevented by a ship’s officer as the hold was filling fast and there was danger of drowning.

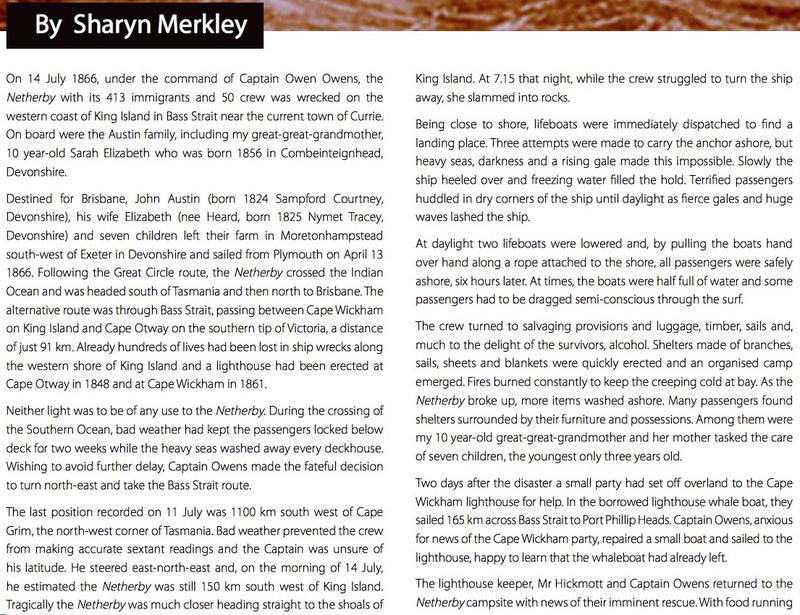

Sarah Elizabeth describes the wreck and waiting for rescue: “All the people came up on deck and were very scared. The Captain tried to calm them by telling them it was a sand bank the ship was stuck on, and it could sink no further, and they all would be able to get off the ship at daylight. He tried talking them into going back below, as some of the masts might break and fall on the deck and kill some of them. Then he gave them some wine to help herd them all back. I stayed where I was all curled up, and I didn’t sleep at all that night. I heard some of the passengers praying to God for help, but most of the others just drank lots of wine and got drunk...

“Early the next morning, the Captain sent one of his Officers ashore to try to find a landing place. When this was done, they put a rope ladder over the side of the ship and started to land us on shore. Women and children were the first to go. The surf was very rough and sometimes the boat shifted away from beneath the ladder, so we had to judge when to drop into the board. Some weren’t very good at judging and fell into the sea, but were quickly plucked out of the water by the sailors. We all managed to reach shore safely but one of the boats was smashed on the rocks.

“The Captain and the crew then managed to get a lot of the ship’s stores of food and other things ashore. They also cut down all the masts off the ship and got the sails. The Captain and the ship’s doctor was the last to leave the ship and they had to wade ashore through the rough water.

“Some of the people had lighted fires and were drying their clothes. There was plenty of wood on the island. I found some fresh water among some rocks on a hill. We lived on damper for a few days, but later on the men shot some wallabies and birds. Father found some pieces of wood and with one of the sails made us a small hut to sleep in from the bitter cold…”

“… l spent most of the days tramping around our part of the island. Some men always carried a gun in case there were blackfellars on the island who might try to spear us. One of the ladies had twin babies and Mother gave her a shawl and some one else gave her two tins of preserved milk...”

“More stuff was got off the ship and Father was given some cocoa and beer. Us kids were given some children’s books with lots of pictures in them. It helped to break the boredom for the next few days, as I couldn’t be bothered walking around anymore seeing the same old places. Father had forbidden us to to off too far on our own…”

“One afternoon, some days later, we all happily clapped when we saw a ship out on the sea coming toward us. Not long after that, another one came. Father got us all together and we all had to walk through the water to the rafts and we got wet and cold. When we got on the ship they gave us some hot soup and some other clothes to wear. We got to Australia the next morning, and got on a train to Melbourne. All the people were very kind to us and gave us lots of gifts and roast beef and fruit, and let us stay in the Showgrounds. We heard that some people were going to stay in Melbourne, but Father wanted to go to Queensland to farm the land that was promised to us. The next day we got on another ship and went to Brisbane. When the ship was going up the river I saw lots of other people and a bird that seemed to be laughing. I thought then that it might not be such a bad place after all.”

The Austins by and large did well in Queensland. Life was hard, clearing land for farming and there were no luxuries, but neither was there the desperate poverty of England and many opportunities opened up for John and his children.

Sarah described life in Queensland:

“Our father bought a draft hose, a second hand dray, harness and some farming tools in Brisbane, and we were going off to Petrie to work the land that was given to us. When we got to Pine Rivers, we found they were flooding and we had to wait days for the water to run off. When we did get there, the land was real nice, be we had to work terribly hard, clearing the land before we could plant crops. I got my first taste of watermelon just before Christmas.

“We lived in a tent for quite some time. There were lots of things we went without, but we never went hungry, we always had lots of tucker on our table. Father hammered two planks together to use as a table, which was under the shade of a large Weeping Willow tree. After a while, Father had two carpenters in to build our house.”

John Austin took the land and worked it, ensuring his family was fed and protected. However there is evidence that at least at one point, he supplemented the farm’s earnings with making moonshine. John Austin senior died in 1903 having made the journey from destitute child of a convict to a respected landowner.

The eldest son, William, also selected land and married 3 times, the first time to Fanny Grant daughter of neighbouring dairy farmers. From his three wives he had a total of 19 children and died in 1935.

The second son Edwin, followed his father into farming and the accumulation of land. In 1868, Edwin applied for homestead selection for 114 acres of land at North Pine River, and 10 years later for conditional purchase of a further 100 acres at Samsonvale – which upon fulfilling the conditions associated passed to his ownership in 1882. In 1902 he selected a further 90 acres at Samsonvale. In 1876, he married Emma Grant, the daughter of neighbouring dairy farmers and had 7 children, one being Bertha, the grandmother of Kate Peters (author of this history. He died age 87 in 1940, living before his death with his married daughter Jenny at Woody Point.

John Henry married in 1878 to Mary Taylor, and seems to have had 15 children before his death in 1947. He certainly engaged in making alcohol and selling it, before eventually being bankrupted. Selena married William Brooking in 1878 and died in 1953. Mary Jane married Robert Aitcheson in 1878 at age 15, had 13 children and died at 90 in 1917. At some stage, James married Mary Lees, although little is known of his life, and he died in 1917.

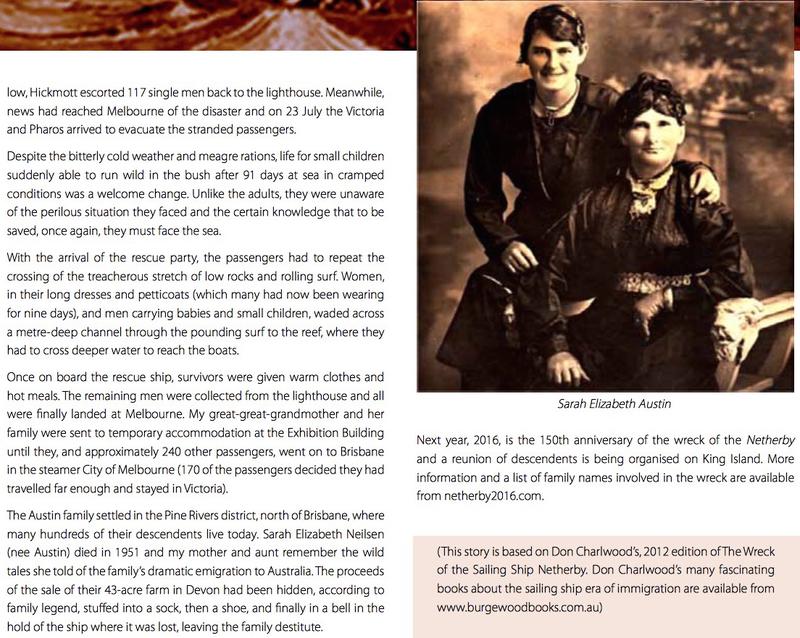

Sarah noted she did not go to school, there wasn’t one to go to. At 20 she married Hans Neilson in January 1875, settled close to her parents and had 10 children. She was a lively character who loved to tell stories of the shipwreck and settlement. She died in 1951 aged 96, although she claimed to be just a few weeks short of 100. She was the great great grandmother of Sharyn Merkley.

It is interesting to note that the descendants of Josias Austin’s second marriage did equally well in Tasmania – testament to the opportunities offered by a new land to those willing to work hard and who survived their tribulations – either convict or shipwreck

Story and photos provided by Kate Peters and Sharyn Merkley descendants of Edwin Austin and Sarah Elizabeth Austin respectively. The source of the quotes for Sarah Elizabeth is the book "The Wreck of the Netherby" by Len Randall; publisher MacGregor, Qld, 2007. It is stated to be the recollection of Sarah Elizabeth Neilson (Née Austin), aged 10 when shipwrecked on 17 July 1866, as told to her grandson Len Randall.

Web Admin Karina: Update 6 Dec 2018. Contacted by Roxanne & Mark Frawley. Mark is descended from John and Elizabeth Austin's son Edwin John Austin. Edwin's son William Charles Austin had a daughter named Isabel, who is Mark's mother.

Roxanne writes: I am the family historian on this side of the family. Funnily enough when I first started researching on the Austins nobody in the family had ever heard about the wreck and what happened to everyone. Nobody had passed the stories down on this side, mainly due to my husband's mother dying very young so we are unable to add anything more. If you are interested in his side of the family tree from Edwin Austin down I would be more than happy to send it on. It is just fabulous that somebody is doing this now. As I said when I started researching many years ago I use to joke about the Netherby because I knew it had left England but could find no records of it landing in Australia. I always said it couldn't have sunk as we knew they had eventually found their way to Queensland. We had a good laugh when we found out it had been shipwrecked as it finally solved the riddle. Too bad we didn't know about the reunion on King Island a couple of years ago as we would have loved to be there.

I will add whatever information Roxanne sends through to me to this page.

Admin update 29 July 2021: Just adding a few things below I had in my folders while I am doing some site updates.

Below screenshots from the website: http://medicalgentlemen.co.uk/patients-and-diseases/heard

Oct 2022: Descendant Sharyn Merkley recently submitted this write up about the Austin family for the Croker Prize for Biography 2022 - Society of Australian Genealogists.

More about the Croker Prize: https://sag.org.au/Annual-Croker-Prize-for-Biography