Passengers stories

by their descendants.

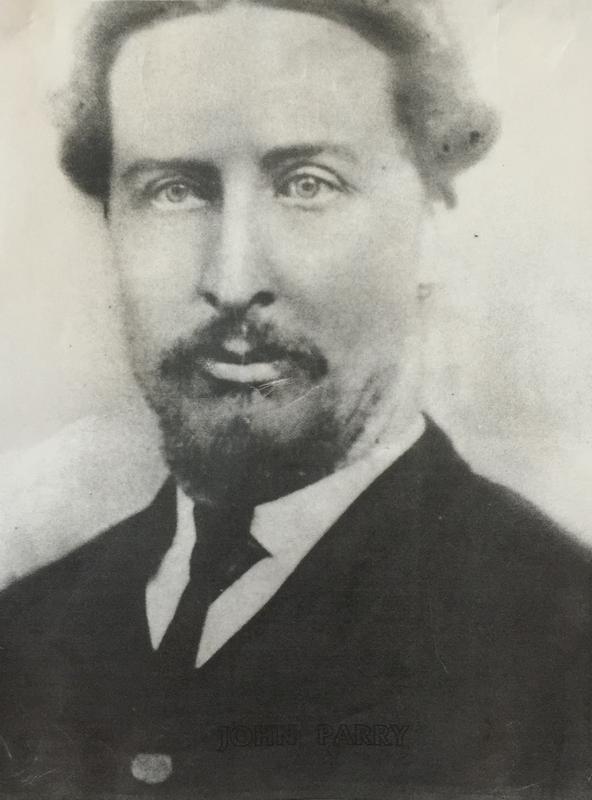

John Parry

The story of: Crew Member, Second Officer John B.H. Parry

a

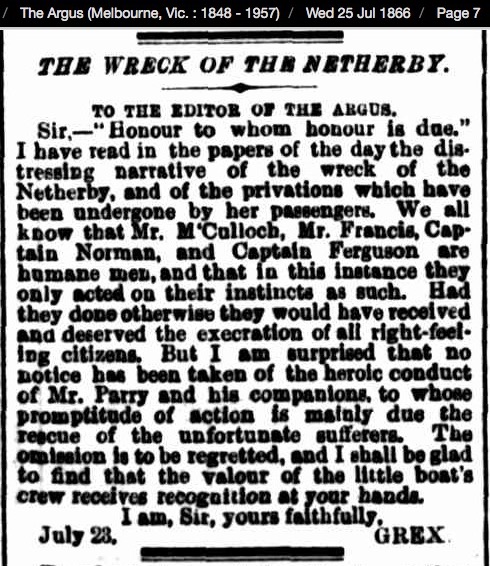

Parry was, without doubt, the hero of the shipwreck story, to whom all of the passengers owed their lives.

5 October 1940, The Argus, Melbourne

NOTES FROM DESCENDANTS:

From the Netherby discussion forum May 2015:

My name is Joanne and my great great grandfather was John Parry, the second officer on the Netherby. His daughter, Lucy Parry married my great grandfather, Ely Richard Lumb and their son was Eli Richard Parry Lumb who married Eileen Thompson. Their son, Richard was my father.

And email from Joanne, 30 October 2016:

What I do know is that John Parry married Mary Carpenter. One of his daughters was Lucy Parry who married Richard Henry Lumb. Their son was Richard Ely Parry Lumb who was my grandfather. He died when my father was about 12 and that is probably why we don’t have the family history. My father was Richard Darrell Lumb and had three children, Stephen Richard, myself and Brendan Timothy.

I can see from Lucy’s birth certificate that her parents were living at Port Melbourne at the time she was born. Lucy was a domestic servant in her mid twenties when she married the 37 year old widowed grazier, Richard Lumb. His mother was also a Carpenter so you wonder if they were cousins. In any event, I may learn more from Helen Vivian’s book as she thought that John Parry may have died an alcoholic which is sad.

The item I put in the chest was the cover of my father’s book, “The Law of the Sea”. He was a legal academic who specialised in constitutional law but I do think it was quite interesting he also wrote about the law of the sea. Interestingly, my family travelled to and from England when I was eight by ocean liner as my father was keen to experience this. It was one of the last ocean voyages (we left in January 1970 and returned in January 1971). We travelled by P&O liners. I probably travelled the same route as the Netherby passengers, around the Cape of Good Hope!

My father and mother were from Melbourne but moved to Brisbane after they married.

Joanne (Parry's great great granddaughter) and her daughter Mehret attended the 150th commemorations on King Island in July 2016 (see above photos).

John Billington Hayes Parry

Born: 1842, West Derby, Lancashire England.

Died: not confirmed – 1882 or 1887, Melbourne.

Second officer on board Netherby.

Eight months before the wreck of the Netherby, Parry was working as a seaman with the Brocklebank line of traders at Whitehaven, Liverpool. On Christmas Day 1865 the fully-rigged sailing merchant ship Tenasserim, which left Liverpool for Calcutta, India, was wrecked off the Irish coast by severe gales. Parry was lucky to have escaped with his life along with thirty three others. It was reported that all thirty three sailors had strapped themselves to the foremast and rigging of the broken and submerged vessel awaiting help for twelve hours, although two of the crew had died.

Parry owed his life to a coxswain named Peter Kavanagh who courageously rowed to the wreck in an open lifeboat from Arklow to rescue the first lot of survivors. Kavanagh later received the Royal National Lifeboat Institute (founded in Great Britain 1824) silver medal for bravery.

On 3 January 1866, Parry, who was back in Liverpool, was issued a “Certificate of Competency as First Mate” from the Lords of the Committee of Privy Council for Trade. It stated “Whereas it has been reported to us that you have been found duly qualified to fulfill the duties of First Mate in the Merchant Service, we do hereby in pursuance of the Merchant Shipping Act 1854 grant you this Certificate of Competency”.

Two months later he was employed with the Blackball Line as Second Mate on the Netherby under the command of Captain Owens, departing London for Australia in April 1866.

The Netherby was wrecked on King Island in the Bass Strait on the night of 14 July 1866. The evacuation of the ship began on the morning of the 15th when Chief Officer Jones and Second Officer Parry finally got a line to the beach and by 9am they were each manning lifeboats and ferrying passengers ashore.

On the 16th Parry and 6 men (William Henry Attwood, Henry P Bluett, Gordon F Springett, Edwin Bellgrove, Robert Stanley and George Joseph Ashton Evans) walked some 48 km over 4 days to the Cape Wickham lighthouse to seek help carrying a note which read “Send help and succour to 500 shipwrecked people from the ship Netherby. Owen Owens, Master”.

The Netherby Gazette pages 59 and 80 refers to them carrying a letter from the Surgeon-Superintendent to the Colonial Secretary of Melbourne (text HERE), and two from the Captain – one for the officer in charge of the lighthouse asking what supply of provisions he could spare in case of urgent need, and the other for the agents of the ship in Melbourne – Bright Brothers, requesting immediate assistance. The Age 23 July 1866 refers to Parry bringing a letter from Dr Webster to the Chief Secretary (Premier James McCulloch) - see link above.

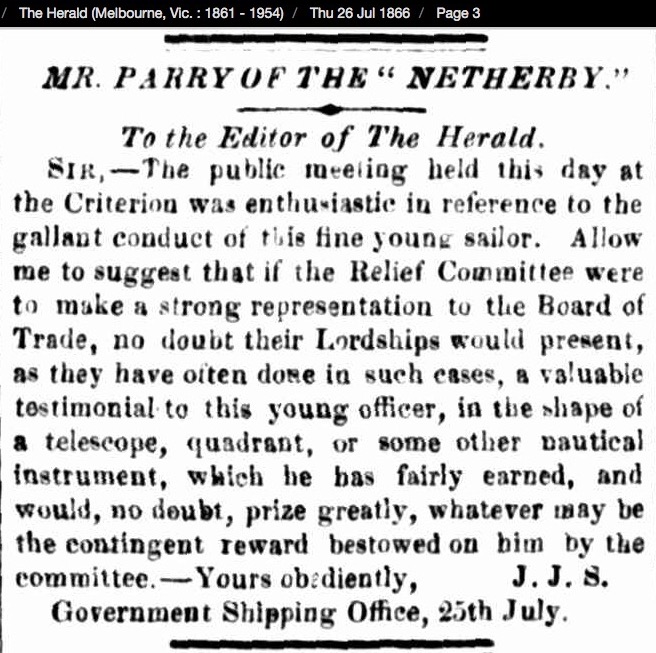

The Herald of 26 July 1866 makes mention of there being in the whaleboat Parry, three other passengers, and a little middy yet in his teens who should not be forgotten. The anonymous passengers letter referenced elsewhere makes no mention of this extra passenger.

The Kilmore Free Press of 26 July 1866 refers to one of the passengers accompanying Parry on the walk as being a Captain in the army.

Upon learning that the cable link with Cape Otway (VIC) lighthouse had been broken for about 4 years, Parry borrowed a twenty three foot long open whaleboat just 2 hours later and set off with passengers Attwood, Bluett and Springett across the Bass Strait. Lighthouse Captain Edward Spong provided them with rations of cooked wallaby and compass and charts.

Passenger Edwin Bellgrove who had walked with them but was unable to join them in the whaleboat – watched them from high up in the lighthouse as they made their way across the strait to seek out rescue. By sundown they were twenty miles on their voyage.

Parry set off on borrowed horse to ride to Queenscliffe (approx. 65 km) (The Age 23 July 1866) reaching there on Saturday evening to telegraph word of the wreck to the Williamstown Harbour Master Captain Charles Ferguson, then rode to Geelong (a further 35 km) to catch a train to Melbourne.

According to The Australasian of 28 July 1866 - A horse and guide having been procured, Mr Parry road a distance of 26 miles to Geelong, where, meeting Mr McGowan, superintendent of the Electric Telegraph department, he telegraphed particulars of the wreck to the Chief Secretary (Honorable James McCulloch, Her Majesty’s Chief Secretary for Victoria, and Premier) and the ships agents. Parry and McGowan then caught the last train to Melbourne and drove to the Chief Secretary’s house at 1.15am.

Kilmore Free Press on 26 July mentions the other three passengers walked from Point Roadknight to Geelong arriving during Saturday night “but we have been unable to learn where they put up and most likely they have gone to Melbourne”.

They intended to steer a north easterly course to pick up the pilot schooner at Port Phillips heads or a fishing boat, but the current carried their boat to the west and they landed on the 21st Parry and his small crew of volunteers arrived at Point Roadknight below the Barwon Heads (*** there is conjecture and misreporting as to the exact landing location which Loutit Bay also referenced in the papers, the closest assumption is that it was near what is now the town of Anglesea on the Great Ocean Road).

(From The Argus and The Age 23 July 1866 - not substantiated in other reports) They came upon an old man minding sheep but he apparently thought they were bushrangers and took to his heels. Finally they overtook him, told their story and were guided to Mr Roadknight’s station where Mr Parry was provided a horse about 6pm on Friday.

The Australasian of 28 July 1866 states ‘Fortunately they succeeded in beaching the boat late on Friday night in a sheltered spot between Point Roadknight and Barwon Heads and luckily fell in with a surveying party under Mr Allan, from whom they received the immediate assistance they needed. A horse and guide having been procured, Mr Parry rode a distance of 26 miles to Geelong..’.

The Evening Post 13 August 1866 mentions the men encountering a party of Government surveyors who were of material assistance to them providing Parry with a horse and a guide).

The Geelong Advertiser of 23 July 1866 quotes Parry as launching the boat from Cape Wickham and steered northwest for the Port Phillip Heads. Heavy weather set in and they expected to be lost, but at last made Roadknight’s Point, where they were hospitably received by Mr AC Allen, who is down there working with a geodetic survey party at Loutit Bay. They got horses, and a letter of introduction from Mr Irving (referred to as Irwin below, and Irvine in Geelong Advertiser 11 Aug) to Captain James Volum and Mr Rice/Bice to send out conveyances for two of the men making for Geelong. Capt Volum and Mr Rice/Bice have used every exertion in their power to forward the objects of the party; and thanks are due to Mr Irving. A vehicle was despatched last night to pick up two passengers who were walking. (In this account 1 passenger is not accounted for if Parry left with a guide by horse, then these 2 were picked up by a vehicle).

(***Karina’s research: Capt Volum, a shipping captain, lived in Geelong and would have logically known the Williamstown Harbour Master Capt Ferguson so the letter of introduction was no doubt to assist in telegraphing the correct person. Mr Bice or Rice – depending on spelling in various papers, may have been Joseph who was the proprietor of the Black Bull Hotel on Malop Street in Geelong and the letter may have been asking him to provide accommodation. Mr Irwin is listed in many news articles through 1866 as being a geodetic surveyor. Mr A C Allen is mentioned in many articles through 1866 as being the Government surveyor).

From a letter to the Queenslander 25 August 1866 – author unnamed but seemingly one of the party in the whaleboat: “We found that the only chance of relief was to go across to Melbourne in a small whaleboat, consequently, Mr Parry, second mate, Messrs. Attwood, Bluett and Springett started off, at 2pm., having pulled safely out of the surf about nine or ten miles. We then hoisted a small spritsail, and got on capitally till night, when it began to rain hard, as well as blow, and to make it worse we found we had no lamp, consequently ever now and then we lighted a match to see how we were steering by a small pocket compass. We spent a most miserable night, all of us being nearly worn out, and it was with great delight we hailed daylight, which brought to our view land, which we made for, but could see no place where we could land, till we came to a small bay, where we thought there was a river. Here we went and, to our delight, saw a small sheltered spot, where we hauled the boat up. We had something to eat (we took plenty from the lighthouse) and then turned in for the night. Next morning we came across Mr Allan’s surveying camp where we were treated most hospitably by both Mr Allan and Mr Irwin, another of the party. They provided Mr Parry with a horse and money, and sent another man to show him the road. The rest of our adventure is already known; as also, how splendidly and nobly the Victorians treated, not only us, but the rest of the unfortunate passengers by the Netherby”.

Parry set off on borrowed horse to ride to Queenscliffe (approx. 65 km) (The Age 23 July 1866) reaching there on Saturday evening to telegraph word of the wreck to the Williamstown Harbour Master Captain Charles Ferguson, then rode to Geelong (a further 35 km) to catch a train to Melbourne.

According to The Australasian of 28 July 1866 - A horse and guide having been procured, Mr Parry road a distance of 26 miles to Geelong, where, meeting Mr McGowan, superintendent of the Electric Telegraph department, he telegraphed particulars of the wreck to the Chief Secretary (Honorable James McCulloch, Her Majesty’s Chief Secretary for Victoria, and Premier) and the ships agents. Parry and McGowan then caught the last train to Melbourne and drove to the Chief Secretary’s house at 1.15am.

Kilmore Free Press on 26 July mentions the other three passengers walked from Point Roadknight to Geelong arriving during Saturday night “but we have been unable to learn where they put up and most likely they have gone to Melbourne”.

Parry then immediately boarded the steam ship Victoria on the Sunday at 11am to assist in the navigation back to the wreck site to rescue the passengers.

(*** Karina's notes: When did he sleep !)

An excerpt (missing a lot of facts) from The Argus 26 July 1866 reads:

“But the most pleasant part of the story yet remains. The conduct of the second mate of the Netherby, Mr Parry, was beyond all praise. Only for his clever and plucky feat, passengers and crew might have perished miserably of cold and hunger. Leaving the scene of the shipwreck on Monday morning to obtain assistance, he made for the lighthouse at the other end of the island, and succeeded in reaching it on Thursday night, which, to a sailor, altogether unaccustomed to bush travelling, and with only a little flour to sustain him, must have proved a painful and harassing task.

Arrived at the lighthouse, that establishment was found strangely unprovided, for a little gin in a toilet bottle was all that it could supply to victual to little whaleboat in which Mr Parry embarked to cross Bass Straits in search of succour for the party on the island.

The danger of the passage having been fortunately escaped, and a good land-fall made, there only remained to ride six-and-twenty miles to Geelong, and set the telegraph to work. The rest was done as our readers are aware.

In this exploit of Mr Parry there were three separate dangers to encounter, and three distinct difficulties to overcome. There were both danger and difficulty in travelling from end to end of King’s Island; also in crossing the straits in a boat; also in effecting a landing on the Victorian coast, and thereafter making his way to some place at which assistance could be obtained. All those Mr Parry encountered, though the last proved very trifling (through his making such a happy land-fall), and we think his pluck, determination, and intelligence, should have some public and substantial recognition.

It may be said that if Mr Parry had not undertaken to task of fetching succour to his companions in misfortune, someone else would; but that is an ungenerous mode of dealing with the matter. Probably some other person would have made the attempt, if Mr Parry had not done so, but that other person might have failed. If he had succeeded as Mr Parry did, then he, and not Mr Parry, would have been entitled to praise and reward.

The three other who shared the perils of the expedition also deserve to have their names rescued from obscurity. Without their assistance Mr Parry could not have accomplished the journey and the voyage in which they were in companions; and in regard to two (sic – should be three) of them, their fortitude and devotion are the more admirable that they were not, as officers of the ship, bound to make extraordinary exertions for the relief of the shipwrecked passengers, and, as landsmen, might have been excused had they shrunk from the perils of the whaleboat voyage. All deserve honour and reward. Mr Parry first, upon whom everything depended, and his three companions in their several degrees.”

Excerpt from The Age 26 July 1866 regarding the public meeting, convened by his worship the Mayor of Melbourne at the Criterion Hotel reads (quoting the Mayor):

“The conduct of the second officer of the Netherby (Mr Parry), who risked his life, and the lives of his fellow passengers in a small life boat, in the passage from King’s Island to Victoria, bringing intelligence of the loss of the ship was most meritorious. Has it not been for his heroic conduct, it was more than probable all on the island would have died from starvation before the disaster could have been made known. (Applause). It was not necessary that he should dwell upon such conduct. It spoke for itself and appealed irresistibly to the best feelings of human natire and it was worthy of the highest commendation. (Applause).

Further quoting Captain McMahon M.L.A “…with respect to the conduct of the second officer of the Netherby, he thought that, when a sufficient sum of money had been raised to provide for the necessities of those urgently requiring aid, the surplus should be devoted to mark the sense of the community of his courageous conduct, as well as the conduct of those who accompanied him. There was no doubt his perilous adventure through the high sea, in a small boat, was an act worth of every consideration, and merited reward.” (Mr Butters seconded the resolution).

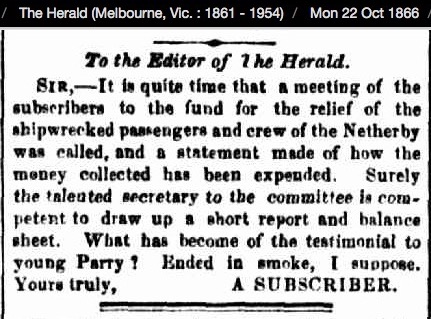

Rev. W. Ornstein moved the third resolution, namely, “That it be in the power of his committee to present to Mr Parry, and to those who accompanied him on the voyage in an open boat from King’s Island, a suitable testimonial of the admiration entertained of his and their heroism in their effort to procure assistance for their shipwrecked fellow seamen and passengers; and that in the event of any surplus remaining of the funds after providing for the reasonable requirements of the sufferers by the wreck of the Netherby, it be in the power of the committee to appropriate such surplus to the relief of sufferers by shipwreck of any vessels sailing from this port.” He said that he did not think they could hold out too much encouragement to those who endeavored to save the lives of others. Thought he knew very little of the circumstances under which Mr Parry had acted, he felt confident that anyone who, in a stormy sea, would venture his life in an open boat to relieve his fellow creatures, was deserving of his warmest thanks and sympathies and that to such a man should be given some public mark of approbation of his conduct. It was necessary, not only as a reward to those who performed such meritorious actions, but as an incentive to others to act in a similar manner. He trusted the subscriptions would be such as to enable to committee to present Mr Parry with a testimonial worthy of his deed; and he felt satisfied from the good beginning that had been made, the committee would be able to show how heroism was appreciated in the city, and how the noble conduct of Mr Parry had gained him the praise and commendation of every right minded and good man. (Applause). He hoped the subscription list would not only enable the committee to do that, but that a surplus would remain as a nucleus of a fund to be applied to any such cases, should they unfortunately occur”.

A rather flowery excerpt from the Cornwall Chronicle 1 August 1866 reads:

"… and they may have all perished – at all events the greater portion of them – had there not been at least one heroic man amongst them who volunteered to pioneer the way across the wintery sea to the great city which was to be their harbor of refuge. Mr Parry, the second mate of the Netherby, was the man who opened the way to the rescue. Accompanied by three others (passengers) and a little “middy” yet in his teens, Mr Parry ventured in an open boat, to cross the angry waters of the stormy sea, and fortunately succeeded in making the coast and putting himself into communication, by means of the telegraph, with the authorities here in Melbourne. The doleful news came to hand late on Saturday night – indeed close to midnight; and yet, by 3o’clock Sunday morning, aid of the most effective kind was in readiness and started by the harbor steamer Pharos, for the scene of the wreck. Not more than four hours had elapsed from the time of the first arrival of the news and the departure of the first instalment of aid, comfort and the promise of safety. Mr Parry quickly followed to town the dispatch which he had transmitted by telegraph, and when the extensive character of the calamity became thus fully known, commensurate measures of relief were at once taken, and in some eight or nine hours after Mr Parry’s arrival in Melbourne he was on board the Colonial Government steamer Victoria hurrying back to the wreck with full supplies of necessities and comforts of all kind …”

“But as advertised to in one of the resolutions at yesterday’s meeting, special provision should be made for substantially recognizing the heroism of Mr Parry, the mate of the Netherby; and funds large enough to effect this object as well as relieve the poor passengers, ought to be collected. Men of Parry’s stamp are to the general throng what genius is to ordinary intelligence – rare specimens of the concentration of the noblest elements of human nature. And when they are met with, and proved by the crucial tests of such experience as furnished by the wreck of the Netherby, they should be prized at their worth and rewarded accordingly. It is to such men that in all great calamities the escape of the suffering throng is due. If they are not present no blow is struck to avert the consequences of the disaster, of whatever kind it may be; and the crowd perishes. If Mr Parry had not the heroism to volunteer to cross the wide and angry waters of the sea which separated himself and his companions from Melbourne, and if he had not at the same time the skill and coolness to carry successfully into practice the promptings of his own benevolent boldness, the vast mass of human beings who were huddled together without food, raiment, or shelter on King’s Island (sic), would have been starved to death with cold and hunger before their wretched condition could have been made known. And the painful narrative of the lighthouse-keeper on that lone island might have been the sole memorial of the wreck of the Netherby. Parry’s heroism, however, saved them; and that heroism should meet with a fitting reward. It is to be hoped, then, that the subscription proposed to be raised will be adequate for the double purpose of relieving the necessitous passengers and presenting a substantial testimonial to Mr Parry, the second mate of the Netherby, together with a handsome gratuity to the men who accompanied him in the boat across the straits. When this shall have been accomplished, as we have no doubt it will in a handsome manner, the Melbourne public may feel satisfied that they have done their duty in a noble fashion.”

On 27 July 1866 it was reported in the Owens and Murray Advertiser that a proposal to strike commemorative medals was made by the Melbourne City Council. Gold for Parry and silver for passengers Attwood, Bluett and Springett. Regrettably nothing came of this proposal.

In The Age 28 July 1866 in writing about the rescue, it states: “The Pharos arrived about

three o’clock, and remained in the offing so as to render any assistance to the Victoria

should it be requisite. Twenty-one of the twenty-three embarked safely, the second mate,

Mr Parry and one seaman refusing to go on board. The Victoria left at about five pm”.

The Evening Post of 13 August 1866 mentions “In due season, the rest of the passengers

and crew were brought away from the island, but Mr Parry and one seaman still remain

there, at their own desire, in order to take charge of such portions of the cargo of the Netherby

as may be washed ashore.”

The Queenslander 15 September 1866 when writing of the salvage operation reads:

“ The second mate of the Netherby, Mr Parry, who so chivalrously crossed from the

island in a whaleboat with the intelligence of the shipwreck, and who so unaccountably

refused to leave again with the Victoria, has taken this opportunity of coming to Melbourne

by the Ben Bolt, and is accompanied by one of the crew, who also remained behind.

Both Mr Parry and this sailor did not stay beside the wreck for a longer period than two

days after the Victoria left. They then went across the island to the lighthouse.”

According to the plaque at Cape Wickham the seaman who remained with Parry

was D McFadzean. For 6 days from 2 August 1866.

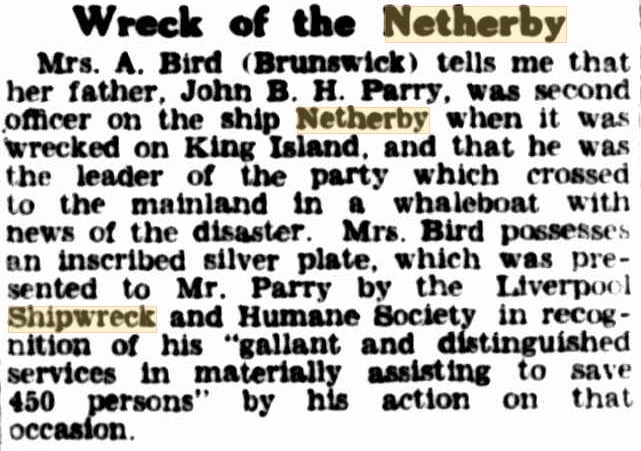

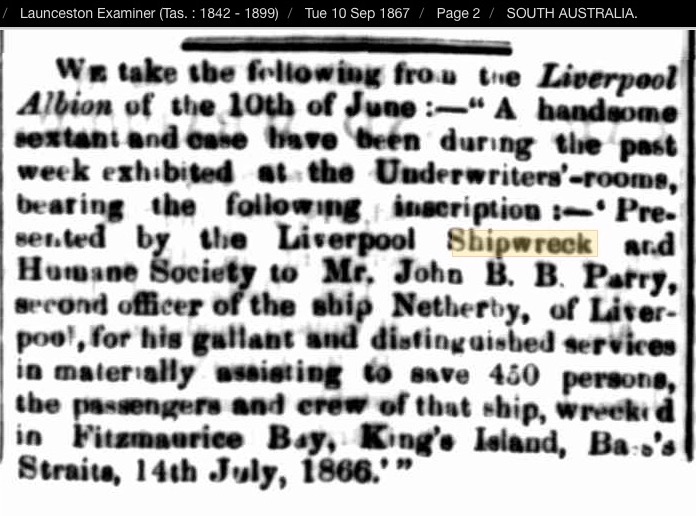

In the Netherby’s home port of Liverpool, England, Parry’s brave efforts were recognised via the presentation of a handsome marine sextant in a brassbound rosewood case from the Liverpool Shipwreck and Humane Society in recognition of his “gallant and distinguished services in materially assisting to save 450 persons” and was exhibited at the Underwriter’s-rooms in Liverpool (Reported in The Leader 17 August 1867 via the Liverpool Albion 10 June 1867).

In time this passed to his daughter, Mrs A Bird, then living in Brunswick, Melbourne, who was two at the time of Parry’s death. In the 1930s it was stolen from her. Possibly it was pawned, for it later came into the possession of a captain with the McIlwraith McEacharn Line. Although he learnt of its theft from Mrs Bird, he refused to part with it; however he sent her the inscribed silver plate from the case.

In a letter to the King Island News of April 1st 1969, she quoted to inscription from it and it was also later reported in The Melbourne Argus 5 October 1940 in the Bygone days column.

Mrs Bird’s letter to King Island News (likely addressed to William Errol Attrill - B 7th Aug 1903 Currie, King Island - D 5th Jan 1974) reads:

11 Reynolds Parade

Pascoe vale South

Melbourne Vict 3055

5.2.69

Mr W.E. Attrill

Dear Sir.

I was advised that you were wanting news of old wrecks. My father was an Officer on Board the ship ”Netherby of Liverpool” when it was wrecked in Fitzmaurice Bay, King Island, Bass Straits. 14 July 1866. He was second Officer on this trip but I have a large Parchment paper with a large blue (dark) <illegible> on it. Stating he had been found duly qualified to fulfill the duties of First Mate in the Merchant Service and was First Mate on the 4.1.66. I had other papers, also one written by the captain describing the wonderful assistance he had performed when the wreck happened. And a Mr Geo Martin J.P. wrote to me from Sorrento 15.10.34. He stated he was four years old and was on the wreck of the Netherby.

He says, of late years I have visited the Island and have been fortunate to secure a copy of <illegible> of the account of the wrecks compiled by a Mr Hickmott Lighthouse Keeper whose assistance my father secured at the time of the wreck <4 illegible words> your father had a hard task set him assisting the wrecked people and that he did it so capably and with such successful results is a tribute to a brave man’s efforts to do his duty. I am sure you are proud to be the daughter of a man such as he was.

Father was presented with a lovely sextant in a brass bound Rosewood base (later years it was stolen. Back in the 1930s).

It was (the wreck I mean) written up in one of the papers here. I think it was the age. And a gentleman wrote to me telling me who had my fathers sextant. “Captain Johns of the McIlwraith McEacharn Line”. I wrote to him and he came to see me. I asked him if he would sell it to me. He told me pretty plainly “NO” and that I would never get it or even see it.

He said it had a silver plate let into the lid with my father’s name and what it had been presented for. He said he had taken it out and would have his own name printed and put on in its place.

He gave it to me and said that is the last you will hear of it. At least I was grateful to receive that much.

Here is what is printed on it.

<Details of the engraving - see picture on the left>

Yours Sincerely

Mrs A. Bird.

The plaque was later given to the care of the King island Museum by Mr Mervyn Bird, where it is installed in an annex building named the Netherby Room.

Having survived two shipwrecks, Parry understandably gave up a life at sea and settled in Victoria. He passed away in his forties and was survived by his wife Mary and at least four children (some sources say 6 with youngest being 2 yrs).

Sources:

Excerpts about Tenasserim by Luke Agati, King Island Historical Society.

5 Feb 1969 Letter to King Island by Mrs Bird

The Melbourne Argus 5 October 1940

The Leader 17 August 1867

Liverpool Albion 10 June 1867

The Queenslander 15 September 1866

The Queenslander 25 August 1866

The Evening Post 13 August 1866

Cornwall Chronicle 1 August 1866

The Age 28 July 1866

Owens and Murray Advertiser 27 July 1866

The Age 26 July 1866

The Argus 26 July 1866

The Argus 23 July 1866

The Age 23 July 1866

The Australasian 28 July 1866

Kilmore Free Press 26 July 1866

The Netherby Gazette

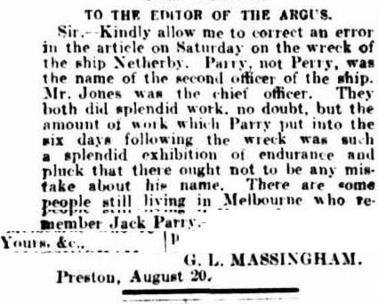

Addition from the website admin Karina. This letter appeared in The Argus 23 August 1927. Written by my great great grand uncle George after he misspelled Parry's name in a previous article about his recollections.

Page containing the articles that had the most detail about Parry's heroism HERE.

References to the reward that seemingly never was.

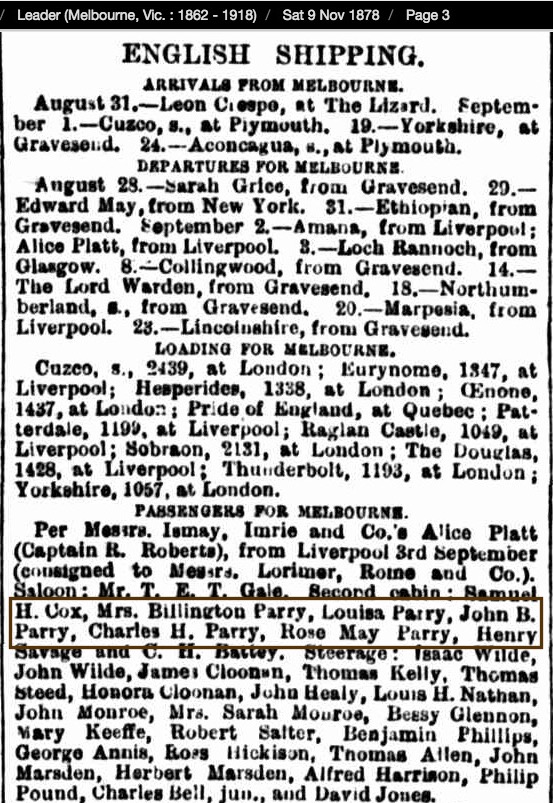

Karina's notes: I haven't learned from research or descendants whether Parry initially headed back to the UK or remained in Melbourne after the wreck. This inbound shipping notice in 1878 shows a Parry family (with Mrs Parry featuring the important Billington name that would be a clue) arriving in Melbourne. Perhaps he first went back to the UK and then eventually immigrated to Melbourne with his family.

** Confirmation from descendant Tania Bell in April 2020 that this shipping register refers to the wife and children of John Parry's brother Mr Billington Parry. (The Billington being used in multiple generations of names it seems).

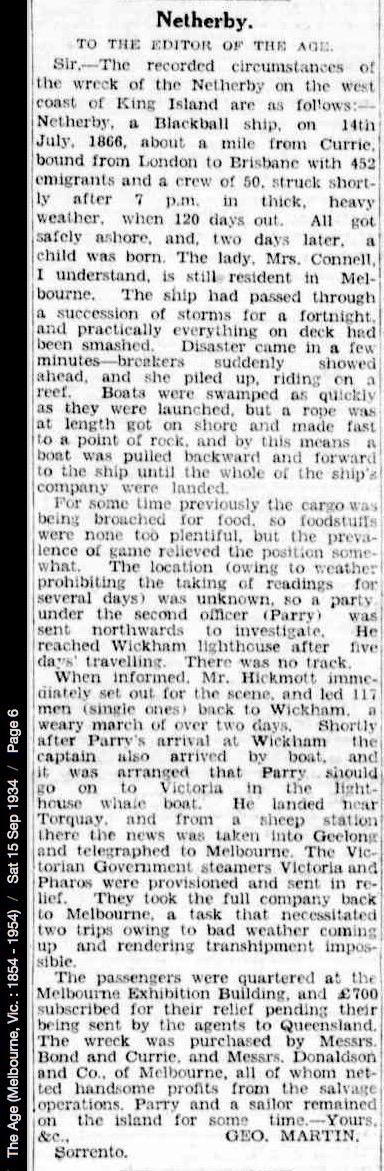

The Age newspaper had a lovely column titled Ships of the Past: Letters from old passengers and others.

It featured peoples questions about names and dates of ships and manifests, and those wanting to make contact with people they met on board, and other people writing in to assist.

The letter on the left in September 1934 was in response to another letter mentioning wrecks on King Island.

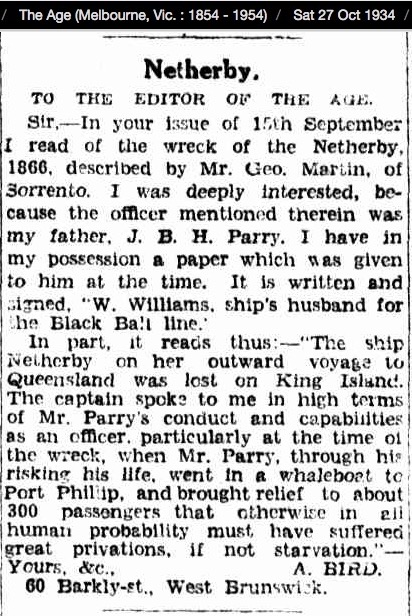

The letter below is by Mrs Bird, Parry's daughter in response to that account.