How the newspapers reported the wreck of the Netherby

The Age Friday, 27 July 1866 The Age, Supplement,

Punctuation, and spelling as in the original.

WRECK OF THE NETHERBY ON KING’S ISLAND

THE STEAMERS VICTORIA AND PHAROS SENT TO THE

ASSISTANCE OF THE PASSENGERS

Intelligence reached the Government about nine o'clock on Saturday night of the total wreck on King's Island of the emigrant ship Netherby, 944 tons, Captain Owens, from Liverpool bound to Brisbane, and the existence of the whole of the passengers and crew, nearly 500 souls, principally women and children, in a state of semi-starvation on the island. The information was brought to town by Mr Parry, second mate of the ship who, in a boat, assisted by two passengers, reached the coast near Mr Roadknight's station, somewhere in the vicinity of Barwon Heads, from whence he proceeded to Queenscliff and communicated to Captain Ferguson, the harbor master, the particulars of the disaster. In passing through Bass's Straits, the vessel struck on the south west point of the Island on Saturday week, and became a total wreck. For some days previous to the catastrophe, the captain was unable to get an observation, and his precise position was therefore unknown. About seven p.m., on Saturday night, the look-out-man reported land ahead, and immediately after the vessel struck heavily. The night being dark and the weather tempestuous, the nature of the coast could not be ascertained, but some notion was formed of its rugged character from the beating of the surf, which was painfully audible. A scene of indescribable confusion followed. The captain, upon ascertaining that the vessel had received irreparable injury, and finding shoal water around him, encouraged the passengers to hope that with the morning some means of landing might be found. With the morning's light the hopes of the passengers revived, upon ascertaining that the coast, though hugged by a heavy surf, was low, and that with care they might reach it in safety. The ship was hard and fast, with her back broken, in shoal water, and as nothing could be done to relieve her, or save anything from her, the captain and crew prepared to land the passengers. This was a work of time, owing to the inability of the boats to get near the shore, the woman and children requiring to be carried through the surf; and the whole of Sunday and Monday was occupied in placing the passengers in safety. It was found impossible to save anything from the ship, and their condition was miserable in the extreme, but, providentially, twenty barrels of floor, which were cast overboard, drifted ashore and afforded temporary sustenance. Upon ascertaining his position, the captain found he had been wrecked on the south-west portion of King's Island, and somewhere in the vicinity of the spot where, some time ago, the Flying Arrow and Catarque were wrecked. The lighthouse belonging to the Tasmanian Government, on the opposite side of the island, and some thirty miles distant, afforded hope of succor; and the second officer, Mr Parry and some passengers volunteered to cross the island and notify to the lighthouse keeper their distress. The lighthouse was reached on Thursday, and a small whaleboat was brought into requisition, in which the officer and two passengers undertook to cross the straits and obtain relief. The boat made the coast, near Mr Roadknight's station, about six p.m. on Friday, and, a horse being provided, Mr Parry reached Queenscliff on Saturday evening, and put himself in communication, through the electric telegraph, with the harbor master at Williamstown, as the representative of the Government.

After passing through the Heads, the breeze freshened and the vessel's head was turned in the direction of King's Island. About four o'clock on Sunday afternoon, a nasty drizzling rain came on, which continued throughout the night, so that when we sighted King's Island light at a quarter to ten p.m., the captain thought it wise to stand away under easy steam, and wait for daylight. When the morning came, we proceeded along the coast, which had a very unprepossessing appearance; the land is low and the shores bounded by rocks, which appeared to be granite. At half-past ten, on rounding a point of head-land, we saw smoke in the distance, and shortly afterwards the hull of the wrecked vessel. At a quarter past eleven we came abreast of it, and dropped anchor about a cable's length from the shore, when the captain of the Netherby went on board in a small boat, which its crew had much difficulty in keeping afloat, one of them being constantly employed in bailing her out. The Victoria's pinnace and cutter were immediately launched and manned, and sent on shore with provisions for those who were to remain behind and to fetch the rest on board.

THE SCENE OF THE WRECK

Is Fitzmaurice Bay, which is almost encircled by reefs of granite rock rising in sharp and serrated peaks above the water. The Netherby lies broadside on to the rocks, about 300 yards from the shore, her head to the northward, with deck to seaward. The masts are cut away, and she is evidently broken-backed, and cannot last long in her present position. She is slightly sheltered from N.W. winds, but so exposed from W. to S. that a gale from that quarter would break her to pieces in a few minutes.

THE VOYAGE AND STRANDING OF THE NETHERBY

This vessel was 976 tons register. She left London on the 1st April, and Plymouth on the 13th. Experienced fine weather, until when near the Cape of Good Hope, very severe weather set in, and very heavy gales lasted for several days; with that exception, the weather had been pretty good. During the voyage there were two births; and two children who were sickly when they came on board, died; these were the only casualties. At half past seven p.m., on Saturday, the 14th inst, the captain was at supper, when Mr Jones, the chief officer, called him on deck, and stated that there were breakers a-head. Captain Owens immediately went on deck, and ordered the helm to be put hard-a-port, which was done, but the vessel immediately afterwards struck, and within an hour her lower deck was flooded. The night was pitch dark, and nothing could be seen but the white breakers around. Shortly afterwards the moon rose and the land was plainly seen. The chief officer took a boat and went to see if a landing place could be found, but came back disappointed; so the shipwrecked people were obliged to wait for daylight, when the mate landed, taking with him a hawser, one end of which he fastened to an anchor placed in the crevices of the rocks, the other end being fastened to the ship. By this, the boats were pulled to and fro, and two thirds of the passengers had been landed when two of the boats were dashed against the rocks and smashed, leaving only one to do the work.

By three o’clock p.m., everybody was ashore but the captain, the surgeon superintendent, and some of the crew, who remained on board to cut away the masts, float the sails ashore, and send provisions which had been got up during the night. Everybody slept on the island that night without having any cover to shelter them from a nasty drizzling rain; the only thing they could do was to light several fires, and lie around them, wrapped in blankets or whatever they could find. Next day (Monday), all hands set to work and erected several tents with the sails and brushwood, which was very plentiful, sufficiently so, indeed, to allow of a compartment being constructed for each family. During the same day, the second mate was sent away to the lighthouse, with letters to the Chief Secretary and the agents of the vessel. All the provisions saved only sufficed to allow of a quarter of a pound of flour a day to be served out to each person, and a little biscuit and tea for the women and children. One day a box of preserved meat was washed ashore, but it was so little that only a few were enabled to partake of it. There were plenty of kangaroo on the island, but after shooting a few the ammunition became exhausted, and the shipwrecked people had to depend on the flour. Very little luggage was saved by any of the passengers; some of them not getting their blankets, some even nothing but what they stood in; and what was saved was damaged by the salt water. They had heard that a steamer was coming to their assistance, from Mr Hickmot, one of the lighthouse staff, who walked across the island to give them the information and bid them be of good cheer. The day after the landing, one woman gave birth to a girl, and both mother and child are doing well.

THE EMBARKATION

The boats of the Victoria were guided by the hawser leading from the wreck to the inner barrier of reefs, where they had to stay. Everywhere around was strewed a quantity of broken utensils and other things, while on the reefs lay the two staved boats, which are now only fit for firewood. In one spot a lot of flat rocks lead from the shore to the reef, forming stepping stones for the poor people to walk upon, but at the end of this they had to cross a channel about twenty yards wide where the water is three feet deep, and through which the surf rolled continuously, making it very difficult, except in the intervals between each roller, to walk. It was melancholy to see the poor women, some of them old and decrepit, dragging themselves through the water, while perhaps alongside of them was the husband and father, with one child on his back and another in his arms. Some of the men took females on their backs, but this was found to be too dangerous in consequence of the surf. After crossing this channel, they came onto a small heap of rocks, by which they were separated from the reef, alongside which the boats were stationed, in a narrow channel about four feet wide, through which the water rolled with terrible force. Men had to be stationed on each side of this passage, to help the women and children across.

When safely fixed on the reef, the poor sufferers (women and children first) were, with some difficulty, placed in the boat. On this reef, waiting for their turn to be placed in the boat, were men, women and, children, all huddled together; some of the latter, who had been, perhaps, brought over by strange men before the mothers, crying piteously for their parents; mothers calling for their children, all wet through; while, to make everything more dreary, the waves, dashing against the rocks, would cast their spray over all, drenching them to the skin, forming a scene truly heartrending. One poor woman, in crossing the channel, had a narrow escape from drowning; a roller coming suddenly against her, she lost her footing, but, before being washed away, a man fortunately caught hold of her and carried her across. Several were in a very weak state, and had to be assisted in the same manner. It was a fortunate thing that there was very little wind, for, as it was, the labor to keep the boats off the rocks was heavy; but, had there been any strong breeze, no boat could have lived, and the poor sufferers could not have received any aid.

The whole circumstances in connection with the-wreck seem miraculous, for had the vessel struck on another reef which ran about a mile into the sea, a little to the left of her, or had there been any¬ wind, all hands on board must have inevitably perished. Altogether, there were 230 souls, placed on board the Victoria. It would have gladdened the most callous hearted to have seen the joyful expression on the countenances of these unfortunate beings. When safe on board, one female uttered the words "Thank God," and immediately fainted; but, on restoratives being applied, she soon recovered. Several others were in a very exhausted state, and for these Captain Norman had ready wine and spirits. Plenty of good hot soup, and bread and beef had been already prepared and was distributed among all as they were severally put on board; this was received with loud expressions of thanks and gratitude. But still they all looked¬ in a pitiable condition, and their wet clothes¬ were taken off, and lines having been put up in the engine room, they were hung there to dry. The poor woman who had been confined on the island, and who was very weak, was, by the kind orders of Captain Norman, placed in his cabin, and everything that the ship afforded was given for the comfort of those who so much needed it.

When 230 had been put into the Victoria, the Pharos arrived and stopped a short distance from us. There were when only about 60 remaining to be taken away as the captain and crew of the Netherby intended to start across the island with provisions for the passengers, numbering 117 single men, who that morning had gone to the lighthouse. The 60 persons at the wreck were therefore placed on board the Pharos. On inquiring whether all was ready, it was found that a few of the first class passengers were still on shore, upon which a message was sent requesting them to come on board as quickly as possible, to which an answer was returned by a Mr Townsend, to the effect that he had not packed his luggage. Another message was sent by Capt. Norman informing him that the vessel would sail, immediately; the answer was, "he would not go with that rabble,'' and he deputed one of the passengers to represent his case to the Government and get another vessel sent for him. Through his obstinacy, a few others also remained behind, but they were willing to come if he would.

THE RETURN

At half past four p.m., everything being ready, the Victoria started on her return, the Pharos following. Soon a great black cloud came hovering o’er and the rain came pattering down; an unfortunate thing for those crowding our deck, who would have no shelter during the dark and dreary night; but in a few minutes the glorious rays of the setting sun shone forth, a gentle breeze set in, the black clouds were carried over the stern, and a fine evening ensued. Shortly after sundown, tea was provided, consisting of meat, bread, tea and potatoes, ad libitum, the latter being enjoyed amazingly after their protracted abstinence from it.

Supper being over, all patiently awaited the drying of their clothes, and during this period they certainly exhibited a motley group. Men and women appeared without shoes or stockings; some of the latter without much more covering than a shawl. When those who possessed any extra clothing had got their garments dry, an hour or so was allowed for a promenade.

It was a beautiful moonlight night, and it was easy to discern the beneficial effects of kindness and good food, by a certain degree of gaiety which soon became visible. As soon as the time for promenading had expired, the women and children were placed on the lower fore deck, where the sailors’ hammocks and several other things were given up for their comfort. The men, and some of the females who preferred it, slept on deck, tarpaulins and spare sails being made available in substitution for blankets. Presently, all was quiet; the day’s exertions and their past troubles operated on the voyagers, and they all slept in the confidence that they were in safety.

The Victoria passed through the Heads again at five o’clock on Tuesday morning, and steamed up the Bay; but when abreast of the lightship at eight o’clock, the captain thought it necessary to anchor for a while, until a heavy fog which prevailed should have cleared away. Accordingly, the anchor was dropped, and we lay still for about two hours. During this time the decks presented a scene like a beehive; all were on deck occupied about something. Here you would see a mother washing her children, there a young girl employed in fixing the feathers on her hat; in another a man would suddenly appear evidently revelling in the thought that he was a gentleman by having changed his corduroy suit for a black coat and beaver hat; while around were the children, well-fed and caring for nothing, running about as happy as possible, and merry as crickets. About eleven o'clock the fog cleared off, the steamer proceeded alongside the breakwater at Williamstown, where all were landed, and taken by special train to Melbourne, and lodged, some in the Exhibition Building and others in the Immigration Depot.

ARRIVAL AT MELBOURNE.

Immediately upon their arrival in Melbourne, the bulk of the immigrants was conveyed to the Exhibition Building, in William-street, by the cabmen assembled in the vicinity of the station, for which service the men unanimously declined to receive any remuneration. About three o'clock they were provided with a substantial dinner, the preparation of which was accomplished by means of a cooking range, improvised for the occasion in the rear of the building, and which proved itself quite capable of satisfying the heavy demands so unexpectedly made upon its resources. Scarcely had the people been housed in their new temporary habitation when presents - not perhaps of much intrinsic worth, but valuable as indicating the general sympathy of the public with the sufferers by the calamity - began to be received.

It is scarcely possible, within the short period which has yet elapsed since the succor of the unfortunate people, to specify the gifts thus presented; but amongst them were a load of apples and other fruits, presented by Mr Hadley, late member of the Legislative Assembly, who rendered valuable assistance throughout the day; a number of periodical publications, the donation of Messrs Robertson and Stephens; and a couple of cases of porter, contributed by the hon. J. G. Francis, for the use of the women, and more especially of those acting as nurses.

One of the most interesting, though not, perhaps, the most important contributions to the little stock of comforts realised by means of these voluntary offerings, consisted of half-a-dozen of new-laid eggs, presented by an elderly lady who thought they might prove beneficial to some of the weaker members of her own sex. Very soon after their arrival at the Exhibition Building, the bulk of the involuntary immigrants was disposed of in a very orderly manner, under the superintendence of Mr Lesley A. Moody. The arrangements for the reception of the people, taking into consideration the brevity of the notice of their arrival, were in the highest degree creditable.

Provision had been made for every contingency capable of being reasonably foreseen, even to the furnishing of a temporary hospital for which, it is to be regretted, some few occupants have already been found. The classification was quite as good as could have been anticipated, under the circumstances, and certainly not inferior to that of Government immigrant ships. At seven o'clock, a substantial tea was provided, and soon afterwards the bulk of the immigrants retired for the night.

The total number of persons received at the Exhibition Building was 287, and the list was made up of 105 men, 86 women, and 96 children; but in addition to this number there were 15 single women sent to the Government Immigrants’ Home. The accommodation of the building, utilised as it was to the utmost, was more than sufficient to meet all the claims made upon it; and the immigrants enjoyed, at the time of retiring to rest, at least a reasonable prospect of more comfort than is generally attainable at sea. It is to be regretted that symptoms much resembling those of English cholera, have been exhibited by some of the passengers, no doubt in consequence of the recent exposure. The gentleman who recently came out in medical charge of the ship Star of India, and Dr. McCrea voluntarily undertook the management of the hospital department, and up to a late hour last evening, there seemed to be no grounds for apprehending any serious illness amongst the shipwrecked people.

In addition to the passengers lodged in the Exhibition Building, several first and second class passengers occupied quarters at Tankard's Temperance Hotel. Amongst them were Messrs Vincent (1st class), Wall, M’Gill, Lockhart, Mr and Mrs Grimes and two children, and Mr Duprez, second class. Some 160 men still remain on the island but they may be expected to arrive some time tomorrow. As soon as the Victoria and Pharos had discharged the immigrants brought up by them the commanders of the respective vessels, in accordance with orders from the Commissioner of Customs, at once proceeded to coal, take in more provisions and prepare for a return to the scene of the wreck to bring off the remainder of the passengers. It is expected they will pass through Heads shortly after daylight this morning. Too much praise cannot be awarded, not only to the Government, but to every officer concerned, for their unwearied attention which has been devoted to providing for the comfort of the shipwrecked people, who appear fully to appreciate the kindness paid them.

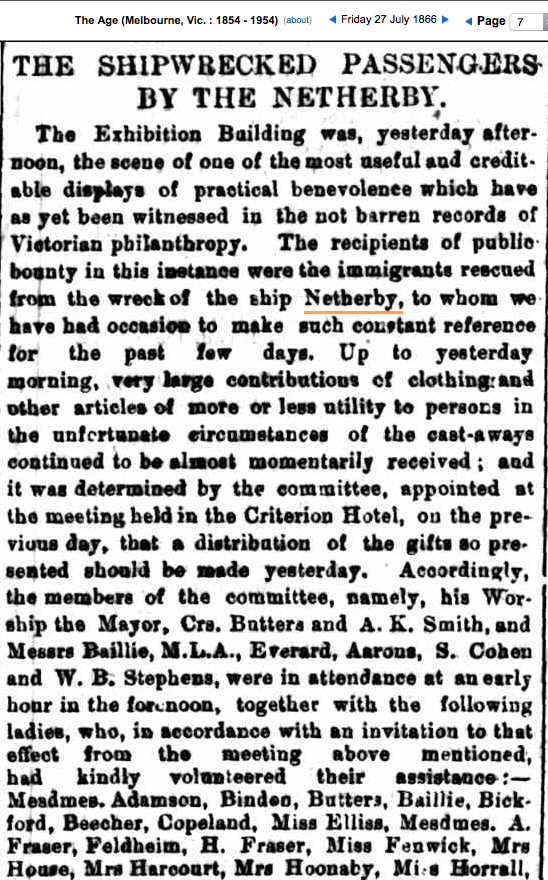

PUBLIC SYMPATHY AND SUPPORT

Whilst the efforts of the Government for the relief of the shipwrecked have merited universal approbation, the benevolent and the charitably disposed of our citizens have not been idle. It was only necessary to make known the sad condition of the immigrants to obtain contributions in and clothing.

A public meeting was held on Wednesday afternoon, at the Criterion Hotel, Collins street, at which the Mayor of Melbourne presided, when resolutions were unanimously passed pledging support, and a committee organised to receive subscriptions to be applied in replacing such articles as were most needed, and otherwise to administer to the relief of the sufferers. Already a considerable sum has been subscribed – close upon £400 – and it is confidently believed that the amount will be trebled before the week closes.

A committee of ladies has been formed to look after the wants of the women and children, and a suggestion has been thrown out which is very likely to be acted upon, that an appeal should be made to the congregations assembled in all places of worship on Sunday next in the city and suburbs.

The heroic conduct of the second mate, Mr Parry, was highly eulogised, and it was resolved that any surplus funds arising from the subscriptions received after the wants of the passengers had been supplied, should be devoted to rewarding his conduct, and that of his associates, to whom, under Providence, the safety of the passengers and crew may be attributed. It was mentioned incidentally that when an appeal was made to the citizens on the occasion of the wreck of the Admella steamer, a surplus of between £500 and £600 was obtained over and above all disbursements, so that something handsome may be expected from the present appeal.

It was furthermore stated that there is at present lying in one of the banks a sum of £3000, subscribed for the relief of the sufferers from the hostilities of the New Zealand natives at Taranaki, which has been left the their Honors the Judges to disburse, owing to some legal difficulties that arose in the appointment of competent persons to authorise the expenditure of the money. It was thought that if a proper appeal was made to their Honors, supported by the Government, that sum might be made available for the establishment of a fund for the relief of shipwrecked passengers, and the suggestion was heartily approved of, and will be acted upon. The surplus of the Admella relief fund was made the nucleus of the Sailors’ Home, an institution which his Worship the Mayor very justly said was a credit to the colony.