George Leake Massingham's Letter.

My ancestor George Leake Massingham, was onboard the Netherby travelling alone, aged just 16. He wrote an extremely descriptive letter home to his mother in England and its transcript is below, in addition to photos of the dodgy old photocopy of the letter I have had since the 1980's.

George was my great great grand-uncle and it always fascinated me that someone so young would be so brave as to travel across the world to a new country on his own.

George went on to be a well known portrait and landscape photographer in Queensland and Victoria, with much of his work retained in the National Library of Australia (see slideshows below). George was interviewed by The Argus (Melbourne) 20 August 1927 about his memories of the shipwreck. There is more information on George and his life HERE.

The original version of the letter was donated by George's great granddaughter Suzanne to the Maritime Museum of Tasmania in 2004 for safe keeping. They have provided me with the below photos of the letter.

By: Karina Taylor, admin of this website.

Brisbane. August 15 1866

Dear Mother

I hope the news of the loss of the Netherby has not reached you or if it has, that it has not made you uneasy as I do not think I was ever safer or more comfortable than I was now. We had a very pleasant voyage out. We had light winds and calm all the cape. Making it very slow and tedious. After that hardly anything but gales and bad weather. One week we had the hatches battened down for five days. So we had no daylight and no fresh air, and if we went on deck to breathe the chances were that a wave would come over and knock us down and we would go below again wet through and as it was bitterly cold weather that was not very comfortable.

On the 14th July we had been looking out for land for two days and it was so dull that the captain could not take an observation and did not know exactly where we were. Someone said they could see land and I daresay had it been a clear day we should have all seen it, at night we all felt it. It was about half past seven when she struck. Then to see them rush on deck groaning and praying. Some who had never prayed before.

They let a boat down but could not get ashore as the breakers were too heavy, when we looked over the side we could see land nearly all round, some places did not look more than two hundred yards off. The captain told us that we could not go ashore till morning. After they had burnt blue lights, and fired the Minute gun till they were tired. At every wave that came the vessel would groan and creak and roll as if she would go over all together and at every roll she gave you could hear the passengers from one end of the deck to the other groaning and shrieking till she settled herself except that now and then she would give thump against the rocks, then they sent some men down to get out some stores, and as soon as they got the hatches off, they saw that she was full of water. So they put us to the pumps, but it was no good. Neither was it necessary, as being hard and fast on the rocks she could not sick any further. So I went down below and put my land order and watch in one pocket and my bible and yours and Nancy's and or or two more likenesses in another.

When I went on deck again it was a little lighter, it had left off raining and the moon was up, a moon only two months old, and by that sickly light we could see the land quite clearly, and very bad it looked. By this time most of the crew were drunk for instead of getting up provisions they had brought up rum, whisky and tobacco. As one man brought up a case, he said "heres some more whisky". Captain Owen's said "yes and I'm afraid whisky will be the loss of us tonight".

As it was now about two oclock, I thought I would go and see if I could get a little sleep, so I went and laid down on one of the sailors bunks and slept till about five, when as it began to get a little lighter I got up. You may be sure I had not undressed that night, it was Sunday morning, but I did not lie in bed waiting to hear the eight oclock bell go, or get up so as to be ready when Walter called for me to go to church with him. At about six oclock the first mate went ashore with a rope and a small anchor which he fixed on the rocks and as one end was made fast on board, they hauled the boat backwards and forwards by it, they first took a dozen single men ashore to help in the landing of the women and children. Then the women went and after that we went as quick as you like.

They told us to make bundles of our most valuable things we had and they would be sent ashore after us, and as I thought that was very reasonable, I went below and made a bundle of all I had, watch, bible, and everything except the "land order" and thats all I saved. I got ashore about eight oclock and I was wet through (we could not get ashore without getting wet up to over our eyes).

I went for a walk along the shore to dry myself. Such a shore I never saw before. Nothing but rocks with pieces of timber strewn in every direction, from the wrecks that had been there for years. As I walked along I saw plenty of wild ducks and other birds that I have never seen before, also traces of animals that I had never seen before which I afterwards found out to be Kangaroos, also some large bones that I could not understand at all, some were so large that I could not lift them, but I was told afterwards that they were Whale bones that had been washed ashore. I saw some very large black birds that were so tame you could get within a yard of them, but they were not tame enough to let me take one back for dinner.

I got back about two oclock and found that all the passengers were ashore and lighted fires, and some were drying themselves while others were building huts of branches of firs and shrubs which were plentiful enough, fourteen of us made a hut together and bought in some some feathery shrub to lay on. At about six oclock they served out a quarter of a pannican of flour to each of us, which was hardly a quarter of a pound. That mixed with a little water and baked in the ashes was all we had for supper that night, after a twenty four hour fast. After supper we laid down to try and get to sleep, and considering that I had very little the night before and the others had had none. You would have thought we might have slept well. But there was no such luck for as the hut being built badly the smoke of the fire blew all ways and we could not breath with out getting a mouth full of it and as it was very cold and we had but one blanket between two of us you may imagine what a pleasant Sunday night it was.

As soon as it began to get light we began to stir. My head ached fearfully from the smoking I ad received it was very cold and I shook from the effects of the wetting I had received and I was very hungry, so altogether I was not in what you may call good condition. While some of us stayed at home to build a good house, others went to chop wood for the fire, some cut branches for us to build with and the rest went down to see what they could pick up on the rocks. The crew were already aboard cutting away the masts and very soon all three masts were overboard, this was done that they might not strain the vessel.

At about nine they got two barrels of oatmeal ashore and served us out a quarter of a pannican each with which we made porridge, and some that had gone to the rocks had brought back about a peck of winkles and limpets, but although the winkles were quite green and rank we thought very nice. By night we had built a tidy shanty we had made as thick as we could to keep the wind out, that night we slept much warmer than we did the night before.

On Tuesday they served us out a little pork, which with a bird one of the party shot, we made a stew, which soon disappeared. The man who brought home the bird, had been out all day with two more men to have shot a kangaroo, but with wandering all day up the hills and down the valleys with nothing to eat, they were forced to return with nothing but a bird, which when plucked, looked more fit carrion than anything else.

Wednesday passed much the same as Tuesday except that I went to fetch some water, which is two miles off, and had a wash, the first I had had since Saturday the fourteenth. I tried to get aboard to see if I could save any of my things, but they would not let me go. At night the men who had gone shooting returned, all but one who was too faint and had sat down to rest, they shot nothing that day, so we had nothing for supper but our allowance, which was a quarter of a pannican of flour.

I forgot to mention that on Monday morning Mr Parry the second mate and a half a dozen of the strongest of the men had started to go round the island in search of a lighthouse, which the captain said was only thirty miles off. You may be sure we were very anxious about the man our shooting party had left behind in the bush, as hour after hour passed and he did not come back, we got quite frightened, but he returned towards morning, he had dropped asleep and when he awoke it was so dark he could not find the way, but when the moon got up by getting on the top of a hill he could see the ship and so he found the way back, but we found out afterwards that the day before, he had helped to get some luggage ashore, belonging to a saloon passenger and instead of diving among us all a bottle of sherry, which he gave him, he kept it himself, and after occasional sips it was hardly to be wondered at that when he sat down to rest he dropped asleep.

Thursday I managed to get aboard the vessel by waiting till the boat had started, then I ran into the water and jumped in, when I got aboard I saw such a scene of destruction as I never saw before. Some of the planks of the deck were three and four inches apart but I made haste into the "tween decks" to get the bundle I had made up on Sunday morning, but it was gone. The scene in the "tween decks" was worse than on the main deck the port lights were broken and the water rushed in at every wave so that the port side being lowest was four feet in water, while boxes had been wrenched open and the best things taken from them and the rest thrown down and were floating in the water, with pieces of the table, bunks, and empty, however as my things were stolen I sat about lifting what ever I saw likely to be useful where we were, I happened to have my old cape and a pair of trousers in my bunk which being a top one on the starboard side was high and dry and as they were folded under the mattress, no one had seen them.

I lived well that day, we had plenty of preserved meat, and biscuits, besides as much sherry and rum as we wanted, there was a large barrel of sherry open on the main deck, that night I took ashore with me (besides a change of dry clothes) three gallons of flour and two of oatmeal, which I had put into water cans, about a stone of raisins and four bottles of rum. The dry clothes I was very glad of when I got ashore for when we left the boat we had got to go through the water up to our knees, it being high tide, and being so loaded and none of our mess there to help me, I fell down full length in the water, more than once but stuck to the things, and as I had taken the precaution to wrap the clothes up in a piece of tarpaulin, I kept them dry.

When I got back I found the men who had gone out shooting had brought in three kangaroos and a little animal I called a duck billed porcipine, so that with the things I had brought there was no fear of us taking any harm for a week at least. You may be sure that night we had a good supper, in fact a better one than we had had since we left Plymouth, although I did not eat much, for I had been eating all day.

On Friday, the lifeboat was got fit for service, and captain Owens and some of the sailors started to go to the lighthouse, for fear that anything might have happened to them that went by land, we watched the little craft sail out of sight, with hopes and fears, for if the first party did not reach the lighthouse, that boat contained our last hope, as there was no hope of a vessel coming near us and they had not got provisions enough ashore to last us all a week, and although they might kill a few Kangaroos, powder was very scarce and retreat before civilisation so very fast, that already they had to go miles to see one.

On Saturday about two oclock we were cheered up by the appearance of a man from the lighthouse who, stated that Mr Parry had arrived on Thursday, with a few of the men that started with them, the rest, they had to send out horses to fetch, and that being a fair wind at the time, they put him with a whale boat at once, for him to make his way to the main land of Australia, and from thence to Melbourne, he also stated that captain Owens had arrived on Friday afternoon, for having a fair wind it only took six hours, but the boat leaked so much that it took two men bail out the water all the way, he had a letter which the captain sent the Dr stating that he might double the allowance for if Mr Parry had reached Melbourne we might expect a steamer to fetch us every hour, and giving him instructions to give the man two pounds for his troubles, but he (Hickmot was his name) refused it saying he had done no more than his duty, he said that Captain Owens wanted to have returned at once but the boat was in too bad condition, so he had undertaken to walk to us to bring the news.

He started at ten oclock at night, promising to get to us by twelve the next day, but it was further than he thought so he did not reach us til two, thus doing in sixteen hours what Mr Parry had taken four days to do. He was a fine fellow, he told us that he had lived on the island for ten years, before he went to the light house, himself, his wife and his pal had been wrecked there some years before, he said he intended to go back that night and that if any of them liked they could go back back with him, and promised a good dinner when they got there, and as many apples as they liked to eat for desert, but they would not let him go back that night so he went from tent to tent telling yarns till late, when someone saw a light at sea, what it was we could not think for some time, but at last we found it was the captain returning. He said he had started in the morning but having wind the poor sailors had to row every inch of the way.

I see it stated in the newspapers here that he bought back three sacks of potatoes, if he did the steerage and intermediate passengers did not see as much as the colour of their jackets.

On Sunday we were informed that the single men were to start with Mr Hickmott on Monday morning back to the lighthouse, as they had fears whether Mr Parry had reached Melbourne or not, and they had not provisions enough for ua all for two days more. So they picked out one hundred and sixteen of us to go. I went though they did not want me to but all my mess were going and I did not care to stay behind, for I do not think I had spoken to a dozen of them during the voyage besides my mess and the sailors.

Sunday afternoon they gave out an allowance of flour and oatmeal to each of them that were going, at eight the next morning we started with Mr Hickmott for a guide. We walked about one hundred yards till we came to a corner. There we stopped and gave a cheer such a three times three as King Island never heard before, three for the camp three for the captain and three for our guide. Then we started in earnest.

Mr Hickmott said that if we done twenty miles that day he would be satisfied, so we climbed along over the rocks in good spirits, when we had gone about five miles, some said they could see the steamer, but it was only a few could see it then at about twelve, we sat for a spell, after having climbed over rocks to any amount and going through sea weed that sank in with us so much, that we had to run through it for fear of sticking fast, we did not mind getting all over filth though it stank horrid, for we were sure to have to go through plenty of water soon after, which must wash it off, when we sat down to dinner we could see the steamer quite plain, but Mr Hickmott advised us not to go back as he said quite reasonably that perhaps the steamer would not be big enough to hold us all and we would certainly find better beds at the light house than those we had left, as for this child I felt desire to go back as I should see certainly see more by going to the lighthouse.

After an hours rest we started again, at night we stopped by a little river and there was no time to build a shanty we had to light a fire and lie down by it, and the fewer that got around the fire the better, three lighted a fire and made our tea together and then lie down by it, somehow or another I managed to sleep very well, although when I woke in the morning the cape I laid on was white with frost.

Mr Hickmott woke us all before it was light, he wanted us to start again by six oclock, it was a very cold morning, the long grass was white frost, and as we walked along knocking our legs against it, it was not warm by any means. We had gone far when someone asked Mr Hickmott how far we had to go, he said about fifteen, which with the twenty we done the day before made thirty five instead of thirty but we found it more like forty five. We walked on till eleven, then we had to wait two hours for the tide to go down, which gave us a good rest, which we wanted for some of them were nearly done up. About half past one we started again and the walking being a little better we done six miles more by three oclock, when some were quite done for.

Our number looked very small, so they counted and found only forty instead on one hundred and sixteen, a few of them were in front but the rest were behind. We had not rested long when we saw a man on horseback come galloping round a point. He was welcomed with a shout, it was Mr Spong the superintendent of the light house. He said that two of the men had walked all night, and got to the lighthouse in the morning, and he said he had started with some biscuits for us as soon as he could find a horse, for they let them run wild.

He said we had only four more miles to go, so on we went but after we got off the sand the hills were fearful, they were so deceiving, for you would get on top of a hill and see the light apparently not more than a quarter of a mile off and began to thank your stars that you only to over that other high hill, and we should be there, but we kept on and on, but that other high hill was still in front of us, we found that four miles and a half was more like seven and a half but I got there about six and was treated very kindly being the youngest of them all. There was a good many of them of them in by twelve at night they kept stopping in one and two at a time all the next day.

The steamer came for us on Wednesday but Mr Spong signalled back that we were not strong enough to go, so they went away but came again on Thursday but got the same answer, they answered back that they could not wait any longer and fixed a place fourteen miles away where we were to be by sunrise the next morning and they would be ready to take us off. So we had to turn out by two oclock in the morning and go back fourteen miles, which we did, and found two steamers, the Victoria and Pharos, I went in the Victoria which reached Williamstown on Friday night, about nine the next morning we landed, and found a train all ready to take us to Melbourne, where we found all the others had been there since Tuesday.

The people very kind and gave us all we wanted. We started again on Tuesday morning, in the City of Melbourne, a fine steamer, we stopped at Sidney where I saw Tom. Going from Sidney to Brisbane they tried to run us ashore again but did not succeed thus we had a narrow escape, we arrived in Moreton Bay on Sunday afternoon. On Monday morning early a small steamboat came to take us up the river, we arrived at Brisbane about noon where I soon found a good brother. Now them little troubles are all over for a little time at least.

Oh hard times come again no more.

I forgot to mention that a little girl was born on the island, there was only two children died on board ship (which considering there was nearly five hundred of us was very good) and two born so with the one that was born on the island after all our misfortunes we reache Australia at last with one more than we started with.

Yours affectionately

George Massingham

First Hand Accounts From Those Who Were There

Tasmanian Maritime Museum Magazine Article Spring 2004, when Suzanne Barton donated the original letter by George to the Tasmanian Maritime Museum.

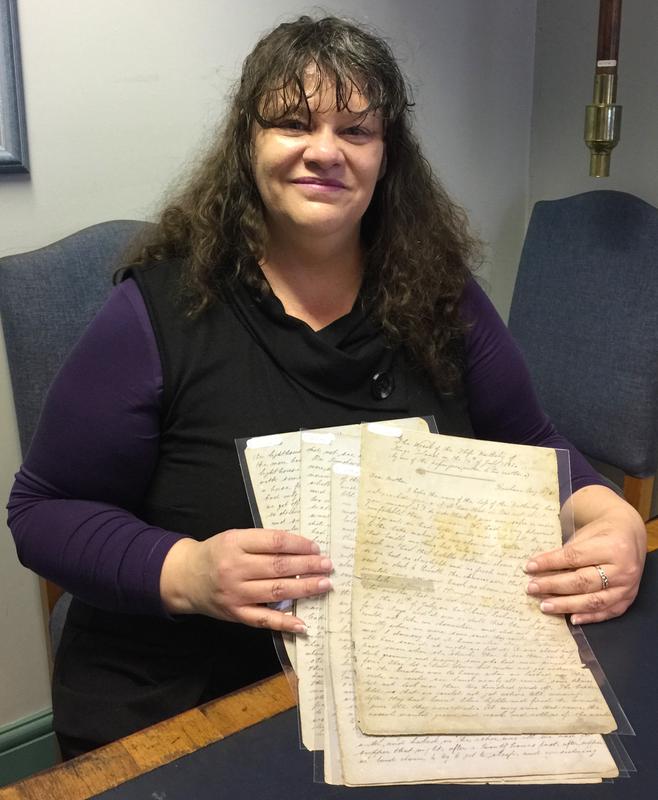

Nov 2016: Karina finally holding in her hand the original copy of George's letter during a visit to the Tasmanian Maritime Museum in Hobart. Very surreal after only ever having an old photocopy of a photocopy for so many decades.